Courses

Q.

What is identity in psychology?

see full answer

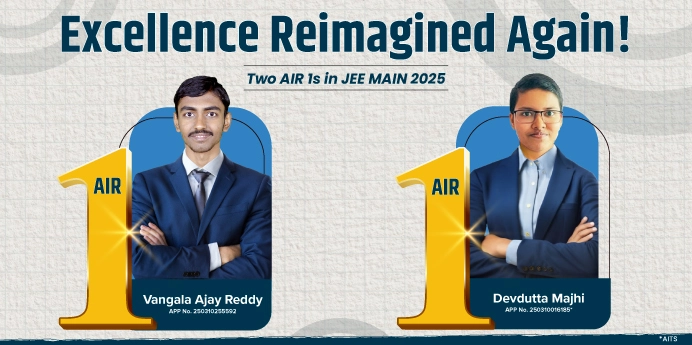

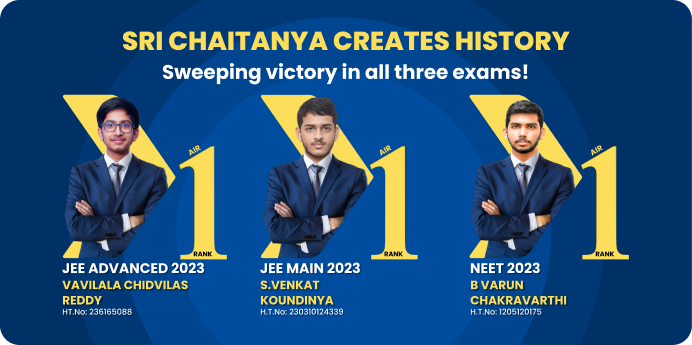

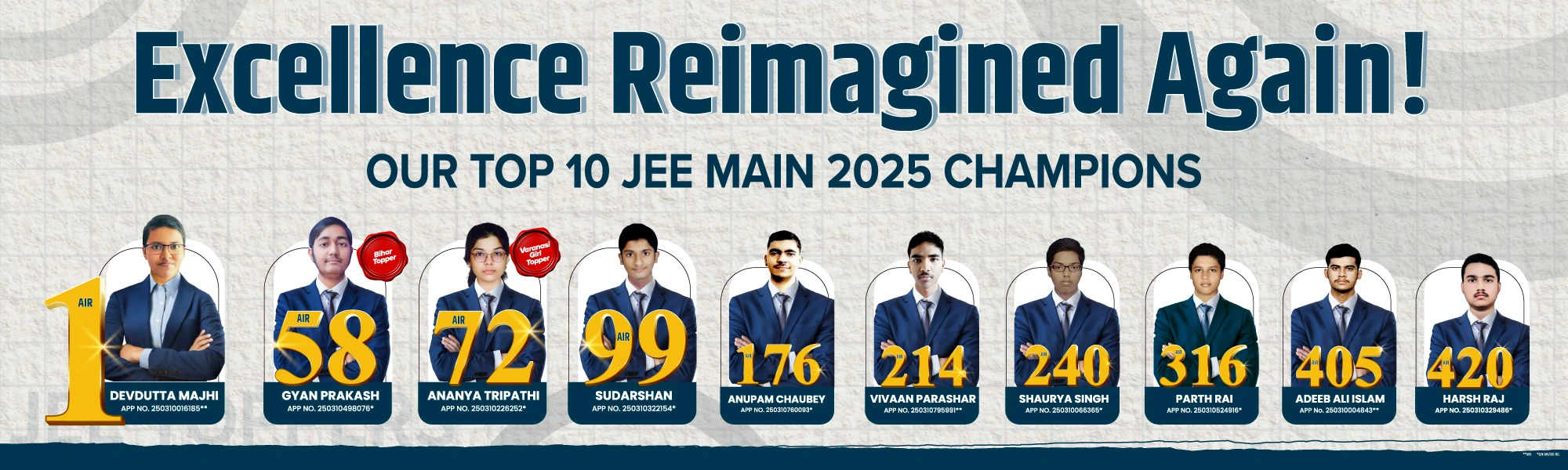

Talk to JEE/NEET 2025 Toppers - Learn What Actually Works!

(Unlock A.I Detailed Solution for FREE)

Ready to Test Your Skills?

Check your Performance Today with our Free Mock Test used by Toppers!

Take Free Test

Detailed Solution

In psychology, “identity” refers to the dynamic, multifaceted sense of who a person is across time and context. It encompasses personal, social, and cultural dimensions: personal identity (unique traits and self-concept) and social identity (membership in groups and social roles). Over the past century, scholars have crafted various frameworks to explain how identity forms, consolidates, and evolves. Below are the core psychological perspectives on identity:

Personal vs. Social Identity (Tajfel & Turner).

Personal Identity: The unique combination of traits (e.g., introversion/extroversion), beliefs (political, moral), and goals that define an individual’s self-concept. It includes the “self-schema”—cognitive structures that store information about personal attributes (e.g., “I am analytical,” “I am creative”).

Social Identity Theory (Henri Tajfel, John Turner): Emphasizes group memberships (e.g., nationality, religion, profession) as central to self-definition. According to this theory, people derive self-esteem from group belonging, so intergroup comparisons (“my group vs. other groups”) drive identity. For example, someone might say, “I am a teacher,” and that social role informs behavior, values, and attitudes.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages (Erik Erikson, 1950s).

Erikson conceptualized identity formation as occurring in “identity vs. role confusion” during adolescence (approx. ages 12–18). However, identity remains fluid, with earlier stages (e.g., “trust vs. mistrust,” “initiative vs. guilt”) laying foundations.

Adolescence (12–18): The individual experiments with different roles and ideologies—peer groups, political views, career aspirations. Successful navigation yields a stable identity; failure leads to confusion and role diffusion.

Later stages (e.g., “intimacy vs. isolation” in young adulthood; “integrity vs. despair” in older age) continue to refine identity as life circumstances shift. Thus, identity is not a static “finished product” but an ongoing process influenced by experiences and stage-specific tasks.

Marcia’s Identity Statuses (James Marcia).

Building on Erikson, Marcia proposed four identity statuses based on “crisis” (exploration) and “commitment”:

Identity Diffusion: Neither exploring choices nor committing—often happens in early adolescence.

Identity Foreclosure: Committed without exploration (e.g., “I will become a doctor because my parents said so”).

Identity Moratorium: Actively exploring alternatives but not yet committed (e.g., trying different majors).

Identity Achievement: Explored and made a commitment (e.g., “[I’ve tried majors A, B, C, and decided to be a psychologist based on my interests and values]”).

Self-Schema & Possible Selves (Markus, 1977).

Self-Schema: Mental structures that help individuals organize and interpret self-related information. For instance, someone with a “creative” self-schema will notice opportunities to paint or write.

Possible Selves: Future-oriented components of identity—ideas of who one might become, who one would like to become, and who one fears becoming. These “possible selves” motivate behavior (e.g., a “successful entrepreneur” possible self may drive one to build skills or network).

Narrative Identity (McAdams, 1990s).

Instead of seeing identity as a static set of traits, narrative theorists argue that individuals create an “internalized life story” to make sense of past, present, and future.

This life story organizes experiences into themes (e.g., redemption, continuity). Over time, the narrative can shift—someone who saw themselves as “the underdog” in high school may rewrite their identity as “successful innovator” after a major career pivot.

Cultural & Intersectional Perspectives.

Cultural Lens: Identity formation is not universal—collectivist cultures may emphasize social roles and family obligations, whereas individualistic cultures focus on personal autonomy and self-expression.

Intersectionality: A person’s identity emerges at the intersection of multiple categories (e.g., race, gender, socioeconomic status). Intersectionality highlights that identity is not monolithic—someone may identify as Black, female, queer, and scientist simultaneously, and each dimension interacts to shape lived experience.

Best Courses for You

JEE

NEET

Foundation JEE

Foundation NEET

CBSE