Table of Contents

Introduction

The eye is considered one of the most significant and sophisticated sense organs that we have as humans. It assists in object visualization as well as the perception of light, colour, and depth. Additionally, these sense organs are similar to cameras in that when light from the outside enters them, they assist humans in perceiving objects. As a result, understanding the human eye’s structure and operation is interesting. It also aids our understanding of how a camera works. The human eye is a coupled sensory organ that reacts to light while also allowing vision. Photoreceptor cells in the retina, such as the corn and rod cells, detect visible light and transmit it to the brain. The brain uses the data from the eyes to evoke perceptions of colour, shape, and depth, as well as movement and other aspects.

Overview

The eye is the most significant optical instrument for detecting light and transmitting signals to the brain via the optic nerve.

It is a vital organ that allows us to see well. It has the ability to detect light, see colours, and distinguish between them. It’s significantly more delicate than even the most advanced photography camera ever created. One of the eye’s most impressive abilities is its capacity to distinguish between things that are at vastly different distances from it. The accommodation of the eye is the name given to this feature of the eye.

The information about the human eye from various physics-related articles is available here. The human eye and its general concepts are important topics in physics. Students who want to flourish in physics need to be well known about the human eye to get deep knowledge about it to do well on their exams. The definition, structure, and functions are provided here to assist students in effectively understanding the respective topic. Continue to visit our website for additional physics help.

Structure and Function of Human Eye

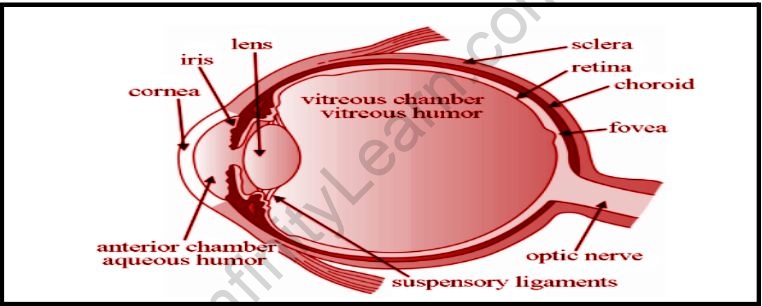

A human eye is almost a spherical ball filled with fluid with a diameter of around 2.3 cm.

The eyes’ construction and functions are intricate. Each eye changes the quantity of light it allows in on a regular basis, focuses on objects close and far, and produces continuous images that are sent to the brain quickly.

The orbit is a bone cavity that houses the eyeball, muscles, nerves, blood arteries, and tear-producing and draining processes. Each orbit is made up of many bones that create a pear-shaped structure.

The sclera is a moderately strong, white coating that covers the outside of the eyeball (or white of the eye).

The sclera is coated with a thin, translucent membrane (conjunctiva) that runs to the border of the cornea near the front of the eye, in the area protected by the eyelids. The moist rear surface of the eyelids and eyeballs is likewise covered by the conjunctiva.

The cornea, the clear, curved layer in front of the iris and pupil, allows light to enter the eye. The cornea protects the front of the eye and also assists in focusing light on the retina at the rear of the eye.

After passing through the cornea, light enters the pupil (the black dot in the middle of the eye).

The amount of light that enters the eye is controlled by the iris, which is a circular, colourful region of the eye that surrounds the pupil. When the environment is dark, the iris allows more light into the eye (enlarging or dilating the pupil), and when the environment is bright, the iris allows less light into the eye (shrinking or constricting the pupil). Like the aperture of a camera lens, the pupil dilates and constricts as the amount of light in the immediate surroundings changes. The pupillary sphincter and dilator muscles work together to control the size of the pupil.

Behind the iris is where the lens is located. The lens focuses light onto the retina by keeping its shape. The lens thickens to concentrate on nearby objects and thins to focus on distant objects due to the action of tiny muscles called ciliary muscles.

Photoreceptor cells

The photoreceptor cells and the blood arteries that support them are both found in the retina. The macula, a small section of the retina with millions of closely packed photoreceptors, is the most sensitive component of the retina (the type called cones). A complex visual image is created by the macula’s high density of cones, similar to how a high-resolution digital camera has more megapixels.

A nerve fibre connects each photoreceptor. The optic nerve is made up of nerve fibres from photoreceptors that are packed together. The initial component of the optic nerve, the optic disc, is located at the rear of the eye.

The image is converted into electrical signals by photoreceptors in the retina, which are transported to the brain by the optic nerve.

Basically, photoreceptors are categorized into two types: cones and rods.

Cones are mostly found in the macula and are responsible for the sharp, detailed centre vision and colour vision.

Rods are in charge of night vision as well as peripheral (side) vision. These cells are more numerous and sensitive to light than cones, but they do not record colour or contribute to detailed central vision in the same way that cones do. Rods are primarily found in the retina’s periphery portions.

It is known that each and every part of the eyeball is filled with fluid and is separated into two sections. The pressure exerted by these fluids aids in the filling out and preservation of the eyeball’s form.

From the inner of the cornea to the front surface of the lens, the front part (anterior segment) is located. It is filled with an aqueous humor-like fluid that nourishes the interior structures. In the anterior part, there are two chambers. The front (anterior) chamber extends from the cornea to the iris. The back (posterior) chamber runs from the iris to the lens. The aqueous humour is normally created in the posterior chamber, flows slowly into the anterior chamber through the pupil, and finally drains out of the eyeball through outflow channels near the iris and cornea.

From the back surface of the lens to the retina, the back part (posterior segment) is located. The vitreous humour is a jelly-like fluid found within it.

The eye has six muscles. They are in charge of handling the eye’s movement. The lateral rectus, medial rectus, inferior oblique, and superior rectus are the most frequent muscles in the eye.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How is the amount of light entering the eye-controlled?

The human body's many parts collaborate to let us see the items in front of us. The brain, as well as some elements of our eye, such as the iris, retina, lens, and optic nerve, are vital organs that allow us to see. Every component has a specific purpose, such as the brain receiving information from the eye via the optic nerve and the lens assisting us in accurately forming the image. Similarly, the iris' role is to control light intensity before allowing a proper amount of light into the eye through the pupil, which is the opening in the middle of the iris through which light enters the eye.

How is the amount of light entering the eye-controlled?

Our left eye sees more of the body's left side, whereas our right eye sees more of the body's right side. Our brain combines the imprints of the two images to form a sense of solidity and distance for the single object. We do, however, get a 180 degree perspective of the surrounding area. That is why nature has provided us with two eyes rather than just one.

What part of the eye makes you see?

Many elements of our bodies work together to aid our vision. Our brain, as well as various elements of our eyes such as the retina, lens, iris, and optic nerve, are vital organs that allow us to see. The lens is made up of transparent, flexible tissue that sits just behind the iris and pupil. Following the cornea, it is the second portion of your eye that aids in focusing light and images on your retina. The lens helps us see by bringing all of the images in our vision into crisp focus. However, situations such as refractive defects, sickness, infection, injured eyes, ageing, and others can result in vision loss.