Table of Contents

Introduction

Every day, we use a variety of acids and bases, such as vinegar or acetic acid in the kitchen, boric acid for laundry, baking soda for cooking, washing soda for cleaning, and so on. Some of these acids and bases only have one hydronium or hydroxyl ion to shed, but the majority of them have numerous ions to shed. Knowing ionization is critical for science students since it shows how atoms’ charges are changed and can aid in explaining how atoms are transformed. In a lab setting, you can see many different examples of ionization, and the effects can be seen in science and in substances that you encounter in your daily life.

Overview

Acids are any chemical that turns blue litmus paper red, has a sour taste in water, reacts with metals to produce hydrogen ions (for example, iron), combines with bases to produce salts, and functions as a catalyst in particular reactions. Sulphuric acid, nitric acid, hydrochloric acid (mineral acid), carbonic acid, sulphonic acid (organic acid), and others are examples.

Ionization is one of the primary mechanisms through which radiation, such as charged particles and X-rays, transfers energy to matter. Polybasic acids are those that ionize and produce more than one proton when dissolved in water. As a result, they’re sometimes referred to as ‘Polyprotonic acids.’ The ionization reaction is carried out in stages. One ionizable proton is emitted at each stage.

Ionization

In general, ionization is any process that converts electrically neutral atoms or molecules to electrically charged atoms or molecules (ions). Ionization in a liquid solution is common in chemistry. For example, neutral hydrogen chloride gas molecules, HCl, react with similarly polar water molecules, H2O, to produce positive hydronium ions, H3O+, and negative chloride ions, Cl–; zinc atoms, Zn, lose electrons to hydrogen ions and become colorless zinc ions, Zn2+, at the surface of a piece of metallic zinc in contact with an acidic solution.

When an electric current is carried through gases at low pressures, ionization by a collision occurs. If the current’s electrons have enough energy (the ionization energy varies by substance), they can push other electrons out of neutral gas molecules, resulting in ion pairs that each includes a consequent positive ion and a detachable negative electron. As some electrons link themselves to neutral gas molecules, negative ions are generated. Intermolecular collisions at high temperatures can also ionize gases.

When sufficiently intensely charged particles or radiant energy pass through gases, liquids, or solids, ionization occurs. Ionization occurs along the routes of charged particles, such as alpha particles and electrons from radioactive elements. Neutrons and neutrinos are energetic neutral particles that penetrate farther and cause nearly no ionization.

The photoelectric effect causes ionization when pulses of radiant energy, such as X-ray and gamma-ray photons, release electrons from atoms. The energetic electrons produced by radiant energy absorption and the passage of charged particles can lead to secondary ionization or further ionization. Because of the continual absorption of cosmic rays from space and UV light from the Sun, the Earth’s atmosphere has a specific minimum amount of ionization.

Ionization Examples

- Whenever sodium and chlorine combine to form a salt, the sodium atom gives up an electron, resulting in a positive charge, while the chlorine atom gains the electron, resulting in a negative charge.

- Hydrochloric acid is formed when previously neutral hydrogen chloride gas and water interact. They generate positively charged hydronium ions and negatively charged chloride ions.

- When acid is used to dissolve metallic zinc, it loses electrons and becomes positively charged.

- Potassium hydroxide plus hydrogen is formed when potassium and water interact. To mix with hydrogen and oxygen, sodium gives up one electron.

- Photoionization is a type of ionization that occurs when radiation interacts with atoms. High-energy radiation causes atoms to lose electrons.

- When electricity passes through a gas at low pressure, it can ionize it, resulting in a positive ion and a single electron.

- During ionization, calcium can lose one electron and become ionized calcium with a positive charge.

- To become a positively charged sodium ion, sodium can lose one electron.

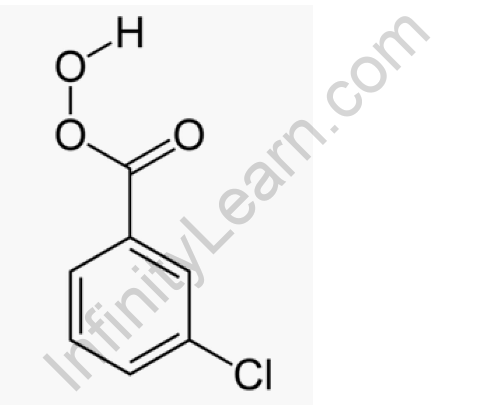

Polybasic Acids

Polybasic acids are those that can produce more than one hydronium ion per molecule, with the dibasic, tribasic, and so on denoting the number of hydrogen atoms that can be replaced.

We can tell that some acids, such as sulphuric acid and phosphoric acid, contain more than one ionizable ion per molecule by looking at them. Polybasic acids are the name given to such acids.

Every day, we use a variety of acids and bases, such as vinegar or acetic acid in the kitchen, boric acid for laundry, baking soda for cooking, washing soda for cleaning, and so on. Many acids and bases that we do not use in our daily lives are utilized in laboratories, including acids such as HCl, H2SO4, and bases such as NaOH, KOH, and others.

Most of these acids and bases only have one hydronium or hydroxyl ion to shed, but the majority of them have numerous ions to shed.

Ionization of Polybasic Acids

Consider the ionization process of a typical polybasic acid as follows.

H2X(aq)⇋H+(aq)+HX-(aq)

HX–(aq)⇋H+(aq)+X2-(aq)

A dibasic acid is dissociated into its constituent ions in this example.

For the aforementioned reaction, the equilibrium constant may be written as,

H2X(aq)⇋H+(aq)+HX–(aq)

Ka1=[H+][HX–]/[H2X]

HX–(aq)⇋H+(aq)+X2-(aq)

Ka2=[H+][X2-]/[HX–]

As a result, the dissociation constant of polybasic acid is the product of the dissociation constants of the constituent ions multiplied together.

Ka=Ka1 ×Ka2=[H+][HX–]/ [H2X]×[H]+[X2-]/[HX–]=[H+2][X2-]/ [H2X]

We can say that Ka1 and Ka2 are the first and the second ionization constants of the acid H2X. Likewise, for a tribasic acid, we have three ionization constants: Ka1, Ka2, Ka3, and so on. Examples of some polybasic acids are H2SO4, H2 S, H3PO4, etc.

Ionization of H2SO4 is:

H2SO4(aq)⇋2H+(aq)+SO42-(aq)

Ka=[H+]² [SO42-]/[H2SO4]

Most inorganic acids react with bases in such a way that one atom of the acid is joined to one atom of a metallic oxide, resulting in monobasic acids.

Some acids, of which the pyrophosphoric is an example, exist in which one atom has the ability to combine with two atoms of the base, and these acids are referred to as dibasic acids. Tartaric acid and malic acid are two examples of this class of acids found in the vegetal and animal kingdoms.

FAQs

What are Polyprotic acids and bases?

Polyprotic acids are acids that in acid-base reactions can shed more than one proton per molecule. In other terms, acids with many ionizable H + atoms per molecule. In the Monoprotic vs. polyprotic acids and bases section, monoprotic acids are contrasted with polyprotic acids.

What is a monobasic acid?

A monobasic acid is one that contains only one hydrogen ion to contribute to a base in an acid-base reaction. Thus, a monobasic molecule only has one hydrogen atom that can be replaced.

Do acids and bases ionize in water?

Acids and bases are soluble in water and prevent water dissociation by raising the concentration of one of the water self-ionization components, such as protons or hydroxide ions. The pH of acidic solutions is lower, whereas the pH of fundamental solutions is greater.